Political Violence in Pakistan

Discovering trends and implications of violent events

The WHO defines political violence as “the deliberate use of power and force to achieve political goals."1

Political violence is often a manifestation of structural violence and inequalities. These structural inequalities include class and ethnic tensions that may lead to protests and wars.2 The state also emerges as a perpetrator of political violence when it uses tactics like repression and torture against its citizens.3

Since its inception, Pakistan has held a precarious position in the global world order.4 It has also been plagued by political violence internally.5 However, there is a dearth of research and analysis regarding the scale of this violence. By using the BFRS Political Violence Dataset (1988-2011) we aim to present a data-centered analysis of political violence and its implications.

The BFRS Dataset further categorizes each political event. Following are some of the major categories:

Overall Trends

Pakistan has faced a turbulent history with political violence from the late 80s.6 This violence was marked by a rise of ethnic and sectarian militants as well as ethnic riots.7In the 1990s, a leading cause of the violence was operations by security forces. In the late 2000s, the violence starkly remerged as a result of pro and anti-judiciary protestors.8

Quantifying casualties shows the scale of violence. Viewing the violence in terms of decades shows that the latter decade (2000-2010) saw a higher loss of lives. There is an especially stark rise in violence post 2008 which reflects a high number of people killed during pro and anti-judiciary protests.9

Considering the number of events in terms of provinces provides some key takeaways. Sindh and Punjab, two of the most economically developed, urban and populous provinces, have the highest number of politically violent incidents compared to other provinces and regions.10

In Punjab, the majority of the violence has been sectarian in nature.11 Shia and Sunni extremist groups have been active in Southern Punjab.12 However, sectarian violence is not restricted to Punjab and is an issue in FATA, Balochistan, and Karachi.13

Karachi alone faced 32% of all sectarian violence that occurred in 2011.14 Zooming in on the high number of incidents in Sindh shows that the majority of them are concentrated in Karachi.

Further investigation into the data regarding Karachi, marks the city as a hub of political violence. Karachi is the most populous city in Pakistan and has a very ethnically diverse population which has made it the center point of ethnic tensions.15 The high rate of violence has also been a result of clashes between sections of the MQM (Muttahida Qaumi Movement) and the state.16

The latter part of the 80s and early 90s was marked by a rise in ethnic and sectarian violence.17The level of violence then fell until there was a stark rise in 1995 which was a result of clashes with security forces.18

Types of Violence

Source: International Growth Centre

Sindh has the highest number of assassinations in Pakistan and most of these are concentrated in Karachi. In fact, 63% of all violent incidents in Sindh took place in Karachi.19

FATA has the highest number of state initiated violence and a high number of militant attacks which reflects the war between the state and militants post 2006.20

Hence, overall trends show that Punjab and Sindh have the highest scale of political violence and zooming in further reveals Karachi as one of the most violent cities and this merits further investigation.

Province-wise Trends

Province-wise Trends of Political Violence (2000-2011)

Since Pakistan witnessed an increase in violent attacks in the latter decade i.e. 2000-2011 of the BFRS dataset, this section aims to focus in that decade when analyzing trends.

Sindh has been the highest bearer of politically violent events. One of the major drivers of political violence in Pakistan is socio-political and economic dominance of Punjab and exclusion of other provinces, particularly Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas22.

One can infer that the events occurring in FATA had the most fatal outcome i.e., 12,602 seconded by Punjab with 6173 casualties. The conflict in Balochistan is driven by a number of grievances and inequities, including “lack of autonomy, lack of Baloch representation in the government and military, and economic oppression”. 22

Since 2007, Pakistan has witnessed a new wave of sectarian attacks committed by militant groups. 22 Moreover, there were waves of political unrest post the 2008 general elections.

After the assassination of Benazir Bhutto in December 2007, there were various attacks in KPK and FATA which targeted “leftist politicians and political rallies” right after the 2008 general elections. The rise in attacks can be evidently witnessed during 2009 to 2010. Violent attacks in KPK rose from 400 in 2007 up to 800 in 2009. Similarly, violent events in Sindh rose from 346 in 2007 to 971 in 2011. Moreover, violent incidents increased in the provinces of Sindh and Punjab in 2010 compared to the previous year, indicating growing urban terrorism in Pakistan.

Trends in Karachi

Exploring Trends of political violence in Karachi

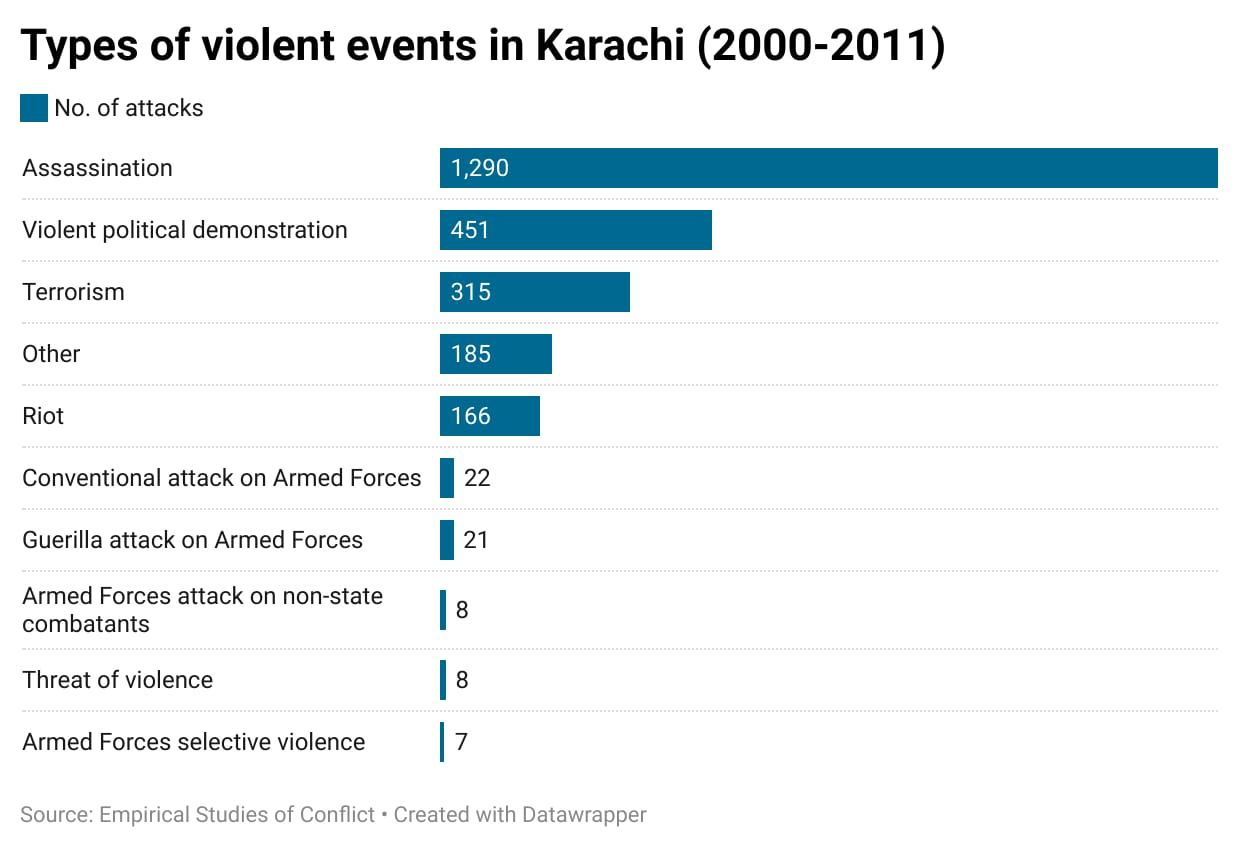

As witnessed above, the number of violent attacks substantially increased in Sindh from 2009 to 2011. Most of these events were concentrated in Karachi which calls for a more in-depth exploration. Karachi is home to 21% of the country’s urban population. Organized crime is rampant and political violence is a norm causing the deaths of thousands of people.23 Moreover, Karachi has suffered the greatest number of violent attacks i.e. 2473 than any other major city in Pakistan.

From 2009-2010, the number of violent incidents in Karachi increased by 454%. This was because of a substantial increase in “sectarian and ethno-political violence, crime and general lawlessness”.21 The Muhajir Qaumi Movement (MQM) has played a pivotal role in the violent conflicts of Karachi. Moreover, numerous criminal groups in the city, some of them backed by local land mafia, also partake in violent acts with support from political parties22.

Looking at the types of violent events reflects the variation in political violence over Karachi. Even political parties are charged with sponsoring “armed cadres who are trained in the use of lethal weapons”. Violence can arise during particular events such as “public meetings, elections and the enforcement of general strikes”. Political violence is usually rooted in ethnic conflict since the most influential political parties operate on ethnic lines. Crime, inter-party rivalry, and ethnic group identity are major parts of the violent politics of Karachi24.

Karachi’s security landscape has been “marred by a combination of ethnopolitical violence, sectarian strife, militancy and gang warfare in 2010”22. The armed violence in Karachi during the first half of the 2010s was caused by “militias maintained by legal political parties”.23

Impact of Political Violence

Impact on Political Behavior and Mental Well-being

There has not been much research into the impact of political violence on the political behavior of citizens during the 1998-2011 time period; however, there is work that analyses how exposure to the decades of violence affected political behavior during the 2018 General Election in Pakistan.

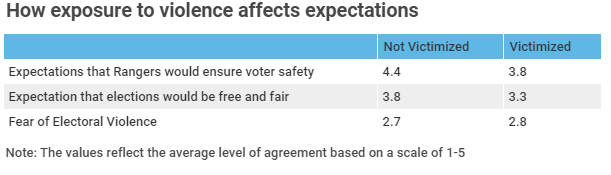

A survey conducted in Karachi shows that individuals who had been exposed to political violence are less likely to trust that the results of the elections will be free and fair, they are also more likely to fear electoral violence. These two factors restrict voter turnout. 25

Source: “Exposure to Violence and Voting in Karachi, Pakistan”, United States Institute Of Peace

Source: “Exposure to Violence and Voting in Karachi, Pakistan”, United States Institute Of Peace

While the scale of violence in Karachi has decreased since 2013, the long history of violence has an impact on existing political behavior.

Data from 2015 shows that individuals who have been exposed to violence on some level are less likely to vote and fear electoral violence.

The study also shows that the type of violent event as well as the perpetrator of the violence, also impacts voting behavior. 32% of the respondents had faced violence at the hands of non-criminal groups (this includes militant groups, political parties, and security agencies). These individuals were significantly less likely to vote.26

Some of the known mental health outcomes of exposure to political violence include PTSD, anxiety and depression. There is a dearth of data and research regarding the impact political violence has had on mental wellbeing in Pakistan. However, there have been studies and surveys conducted in specific areas.

Terror attacks not only trigger immediate panic but also have long term psychological effects. A survey conducted by Pak Institute For Peace Studies aimed to gauge the psychological effects of exposure to terrorist attacks. 61.5% of respondents revealed they felt a high degree of uneasiness during waves of terror attacks. This indicates that terror attacks trigger high levels of stress and anxiety.27

The survey also focused on children and 32% of the respondents reported that children are highly restless due to terror attacks and 37% of them reported that children have become highly fearful of leaving their homes. This survey was conducted in Lahore, Rawalpindi and Peshawar and has low external validity.28

However, it indicates that terror attacks have psychological effects on adults and children, and there is a need to take measures and provide mental health services to alleviate these psychological effects.

Another study conducted on SWAT valley, a region with high levels of terrorism and violence, revealed that Pakistan’s existing mental health setup is not sufficiently equipped to deal with the psychological effects of terrorism. A survey of 600 young people in Swat showed that most had experienced 16 out of 17 symptoms of PTSD.29

A 2009 World Health Organization report on mental health revealed that only 0.40% of Pakistan’s total expenditure on health is dedicated to mental health. 30

As of 2021, Pakistan still does not have a proper national strategy to achieve the WHO's recommendations for a mental health action plan.31

Current situation of political violence in Pakistan

A steady improvement in the country’s security over the last decade

There has been a overall decrease in the number of violent events, people killed, and people injured from 2011-2019 indicating an improvement in the country’s security.

Even in 2020, this decreasing trend in the incidence of violent events has continued in Pakistan that has been ongoing since 2014; the year experienced a 36% decrease in the number of terrorist attacks as compared to 2019.32

However, despite the fact that there has been a decline in the number of events of political violence in the last decade, the operational capabilities of terrorist groups are still intact. Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan and the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) were the two major sources of instability in 2020 who carried out a significant number of attacks throughout the year.33

There has also been no significant shift in the security landscape of the country in light of the Covid-19 outbreak.34 In certain provinces like Balochistan and KPK however, surges in political violence, like terrorist attacks, have been witnessed in certain time periods causing political unrest. In the Balochistan region, the presence of multiple active insurgent groups was the source of these attacks and they were seen expanding their area of operation over the region as well. 35

Projections for 2021

Political violence related challenges and responses are likely to be surrounding CPEC and the safety of the Chinese nationals residing in Pakistan in 2021.36

The state however, will continue to give low priority to tackling religious extremism despite the rising trends of religious and sectarian hatred and communal violence. These extremist groups will continue to exploit this weakness of the government and the state’s belief that these groups can be managed through political tactics alone without devising a strategy to control their extremist narratives. 37

Policy Recommendations

Frequent incidence of political violence has become a permanent feature of Pakistani citizens’ lives leading them to become desensitized to a great extent. Mostly people do not even realize the profound impact this is having on them and their children’s lives.

In light of the fact that political violence has significantly decreased now, there is still a need for certain interventions to further improve the security situation in the country and to limit its mental impact on adults and children for which the following recommendations should be noted:

Controlling political violence

- Baluchistan being most critical in terms of security currently, the government needs to formulate a complete plan for the reintegration of insurgents in order to resolve the Baloch insurgency. 38

- The state needs to ensure the establishment of an empowered, resourced police force in order to have a strong counter-terrorism strategy.39

- As research points to a higher effectiveness of police forces as compared to military forces in combatting violence, a representative police force which includes women is vital in preventing violent organizations from flourishing and establishing trust between civilians and police. 40

- It is also imperative to create awareness and educate people about terrorism-related interventions by the government to diminish confusion about their efforts in combatting violence.41

- Increased and alternate security forces other than Rangers around important events like national elections to ensure voter turnout and mitigate fear about electoral violence.42

Countering mental and emotional impact on citizens

- Further research on psychological impacts of political violence across multiple areas of citizen's lives is needed along with an increase in the knowledge of such effects of political violence particularly for mental health professionals in conflict areas.43

- News and media outlets need to review the manner in which the news is being broadcasted in order to minimize violent content like graphics and videos. 44

- Special care needs to be taken with regards to children’s exposure to such incidents to prevent any negative impact on their health.

- Maintenance of sound collective social and political functioning which has a positive impact on the mental health of those who have experienced political violence.45

- Increased cognizance on the part of the state and military of possible negative effects of violent attacks on criminal actors—including spillover effects, through having family members be victimized — as when violence is perpetrated by state actors the effect on political behavior is amplified.46

- The national healthcare policy needs to incorporate a mental health care system that is able to address the psychological effects of violence. One way of doing this is for the government to encourage collaboration between the public healthcare sector and existing professional mental health bodies and NGOs.47

References

1Sousa C. A. (2013). Political violence, collective functioning and health: a review of the literature. Medicine, conflict, and survival, 29(3), 169–197, Jul 1 2014. Accessed April 25, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3801099/

2Cairns E, Darby J. The conflict in Northern Ireland: Causes, consequences, and controls. [10.1037/0003-066X.53.7.754] American Psychologist. 1998;53(7):754–760.

3Robben ACGM. Political violence and trauma in Argentina. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

4“Pakistan: A Political History”, Center For Global Education, https://asiasociety.org/education/pakistan-political-history

5Ibid.

6Jacob N. Shapiro and Rasul Baksh Rais, “Political Violence in Pakistan 1988-2010”, International Growth Centre. https://www.theigc.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Shapiro-Et-Al-2012-Working-Paper-1.pdf

7“Karachi: Pakistan's untold story of violence”, BBC, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-south-asia-12850353

8Ibid

9Ibid

10 Jacob N. Shapiro and Rasul Baksh Rais, “Political Violence in Pakistan 1988-2010”, International Growth Centre. https://www.theigc.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Shapiro-Et-Al-2012-Working-Paper-1.pdf

11Huma Yusuf, “Sectarian violence: Pakistan’s greatest security threat?”, Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centerhttps://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/151436/949e7f9b2db9f947c95656e5b54e389e.pdf

12Ibid.

13Ibid

14Ibid.

15“Karachi: Pakistan's untold story of violence”, BBC, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-south-asia-12850353

16Ibid.

17Ibid.

18Ibid

19Jacob N. Shapiro and Rasul Baksh Rais, “Political Violence in Pakistan 1988-2010”, International Growth Centre. https://www.theigc.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Shapiro-Et-Al-2012-Working-Paper-1.pdf

20 Ibid

21PIPS. "Pakistan Security Report 2010." Pak Institute For Peace Studies (PIPS) (2011): 74.

22AsiaFoundation. "The state of Conflict and Violence in Asia." asiafoundation.org (2017). https://asiafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Pakistan-StateofConflictandViolence.pdf

23Rehman, Zia Ur. The News. 30 May 2020. 20 April 2021. https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/665136-study-identifies-urban-drivers-of-political-violence-in-karachi

24Gazdar, Haris and Hussain Bux Mallah. " Informality and Political Violence in Karachi." Urban Studies (2013): 1–17 https://sci-hub.mksa.top/10.1177/0042098013487778

25Mashail Malik and Niloufer Siddiqui, “Exposure to Violence and Voting in Karachi, Pakistan”, United States Institute Of Peace, June 19, 2019. Accessed April 1, 2021. https://www.usip.org/publications/2019/06/exposure-violence-and-voting-karachi-pakistan

26Ibid.

27Amjad Tufail, “Terrorist Attacks and Community Responses”, Pak Institute For Peace Studies (PIPS), Jan 1, 2010. Accessed April 1, 2021.

28Ibid.

29Khalily MT. Mental health problems in Pakistani society as a consequence of violence and trauma: a case for better integration of care. Int J Integr Care. 2011;11:e128. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3225239/

30“WHO-AIMS Report on Mental Health System in Pakistan”, World Health Organization and Ministry of Health Pakistan. https://www.who.int/mental_health/pakistan_who_aims_report.pdf

31Rahul Basharat. “Pakistan still spending below 1pc of GDP on health.” The Nation, https://nation.com.pk/01-May-2020/pakistan-still-spending-below-1pc-of-gdp-on-health

32Muhammad Amir Rana, “Security projections for 2021”, Dawn, January 24, 2021. Accessed April 19, 2021. https://www.dawn.com/news/1603286

33Ibid.

34Ibid.

35Ibid.

36Ibid.

37Ibid.

38“ Pakistan Security Report 2019”, Pak Institute For Peace Studies (PIPS), Jan 5, 2020. Accessed April 17, 2021.

39“Revisiting Counter-terrorism Strategies in Pakistan: Opportunities and Pitfalls”, International Crisis Group, July 22, 2015. Accessed April 19, 2021. https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-asia/pakistan/revisiting-counter-terrorism-strategies-pakistan-opportunities-and-pitfalls

40Allison Peters And Jahanara Saeed, “Promoting Inclusive Policy Frameworks For Countering Violent Extremism”, Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security, December 2017. Accessed April 25, 2021.

41Amjad Tufail, “Terrorist Attacks and Community Responses”, Pak Institute For Peace Studies (PIPS), Jan 1, 2010. Accessed April 1, 2021.

42Mashail Malik and Niloufer Siddiqui, “Exposure to Violence and Voting in Karachi, Pakistan”, United States Institute Of Peace, June 19, 2019. Accessed April 1, 2021. https://www.usip.org/publications/2019/06/exposure-violence-and-voting-karachi-pakistan

43Sousa C. A. (2013). Political violence, collective functioning and health: a review of the literature. Medicine, conflict, and survival, 29(3), 169–197, Jul 1 2014. Accessed April 25, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3801099/

44Amjad Tufail, “Terrorist Attacks and Community Responses”, Pak Institute For Peace Studies (PIPS), Jan 1, 2010. Accessed April 1, 2021.

45Sousa C. A. (2013). Political violence, collective functioning and health: a review of the literature. Medicine, conflict, and survival, 29(3), 169–197, Jul 1 2014. Accessed April 25, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3801099/

46Mashail Malik and Niloufer Siddiqui, “Exposure to Violence and Voting in Karachi, Pakistan”, United States Institute Of Peace, June 19, 2019. Accessed April 1, 2021. https://www.usip.org/publications/2019/06/exposure-violence-and-voting-karachi-pakistan

47Khalily MT. Mental health problems in Pakistani society as a consequence of violence and trauma: a case for better integration of care. Int J Integr Care. 2011;11:e128. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3225239/