The COVID-19 Vaccine Fairytale

Economic losses, human life, and healthcare provisions - What has really influenced rapid vaccine development?

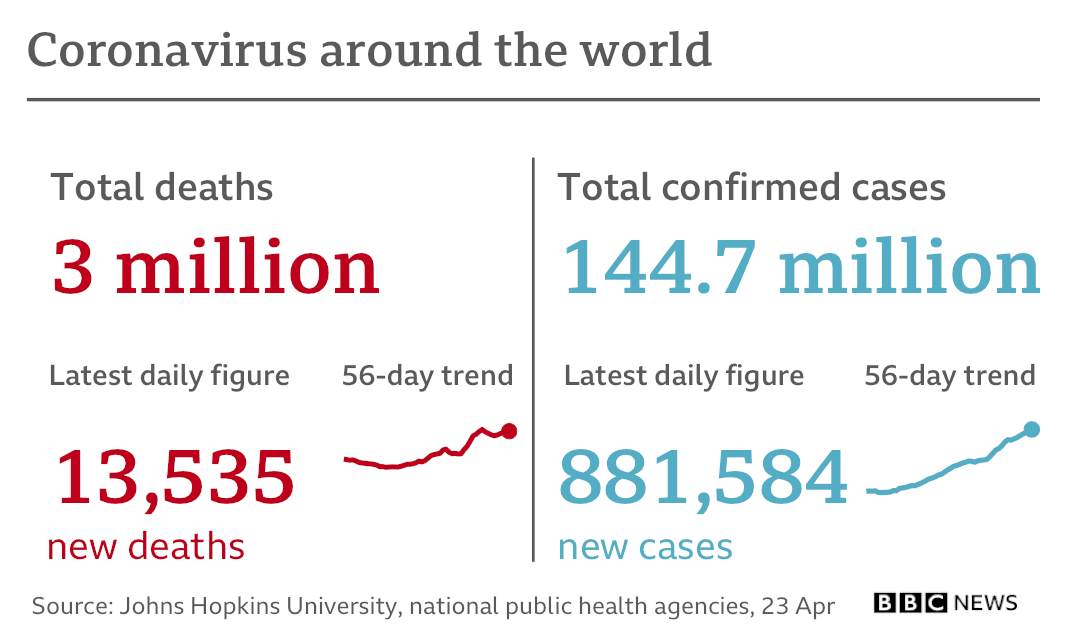

The Coronavirus as it stands.

The Coronavirus as it stands.

An initial timeline of the emergence and spread of the virus:

Week of Jan 18–Jan 24: First Cases Appear in the United States and Europe; The Closing of Wuhan.

Week of Jan 25–Jan 31: First Cases Appear in Many More Countries; Travel Bans Spread.

Week of Feb 1–Feb 7: First Deaths Outside China; Coordinated G7 Response; Chinese Stock Markets Plunge.

Week of March 14–March 21: China reports no new Coronavirus cases for its Third Consecutive Day; Italy becomes the country with the highest death-toll; President Trump signs the Families First Coronavirus Response Act into Law.

Week of March 22–March 29: Nearly one-third of the world's population is living under coronavirus-related restrictions; Japan Postpones 2020 Summer Olympics; the WHO warns there is a "significant shortage" of medical supplies.

Week of March 30–April 4: Worldwide coronavirus cases exceed one million; over 10 million Americans file for unemployment.

Week of April 13–April 20: China reports its first economic contraction in a decade.

Week of April 21–April 28: President Trump suspends immigration; China pledges $30 million to the WHO for COVID-19 related healthcare facilitation.

The Lockdown:

The COVID-19 pandemic created a public health crisis that ultimately changed all aspects of everyday life, including education, work-life balance, and, most drastically, the economy. The damage was unprecedented in speed and in its ferocity. To stop the spread of the disease, most states ordered non-essential businesses to shut down, and, as a result, supply chains were disrupted, workers were furloughed and then laid off, and demand plummeted.

Figure 1: Trajectory of Cases in Israel and Imposition of Lockdown.

The Vaccine:

Sky News’ dedicated COVID-19 analysis wing reports that a stark divide between COVID-19 vaccine roll-outs in the world's wealthiest and poorest nations has emerged. For every dose of a COVID-19 vaccine administered in lower-middle-income countries, such as India and Egypt, the wealthiest nations have given out 23 (Our World in Data, UBS, and Sky News).

By February 2021, upwards of 151 million doses had been administered around the world, according to Our World in Data. Out of these, a total of 65% of doses were concentrated in the US, the UK, and China. To put this into context, it leaves the majority of the world's countries not having had a single vaccine dose while high-income countries steam ahead. Figure 2: Trajectory of Cases in the UK and Imposition of Lockdown.

There is weight around the notion that vaccine procurement has been largely economically charged, with many purchase agreements being made by countries well before vaccines had even been approved. These countries being particularly those which fall into the middle to high-income brackets.

What then does that tell us about the nature of the global pandemic and the power dynamics at play in the race for vaccine development and administration?

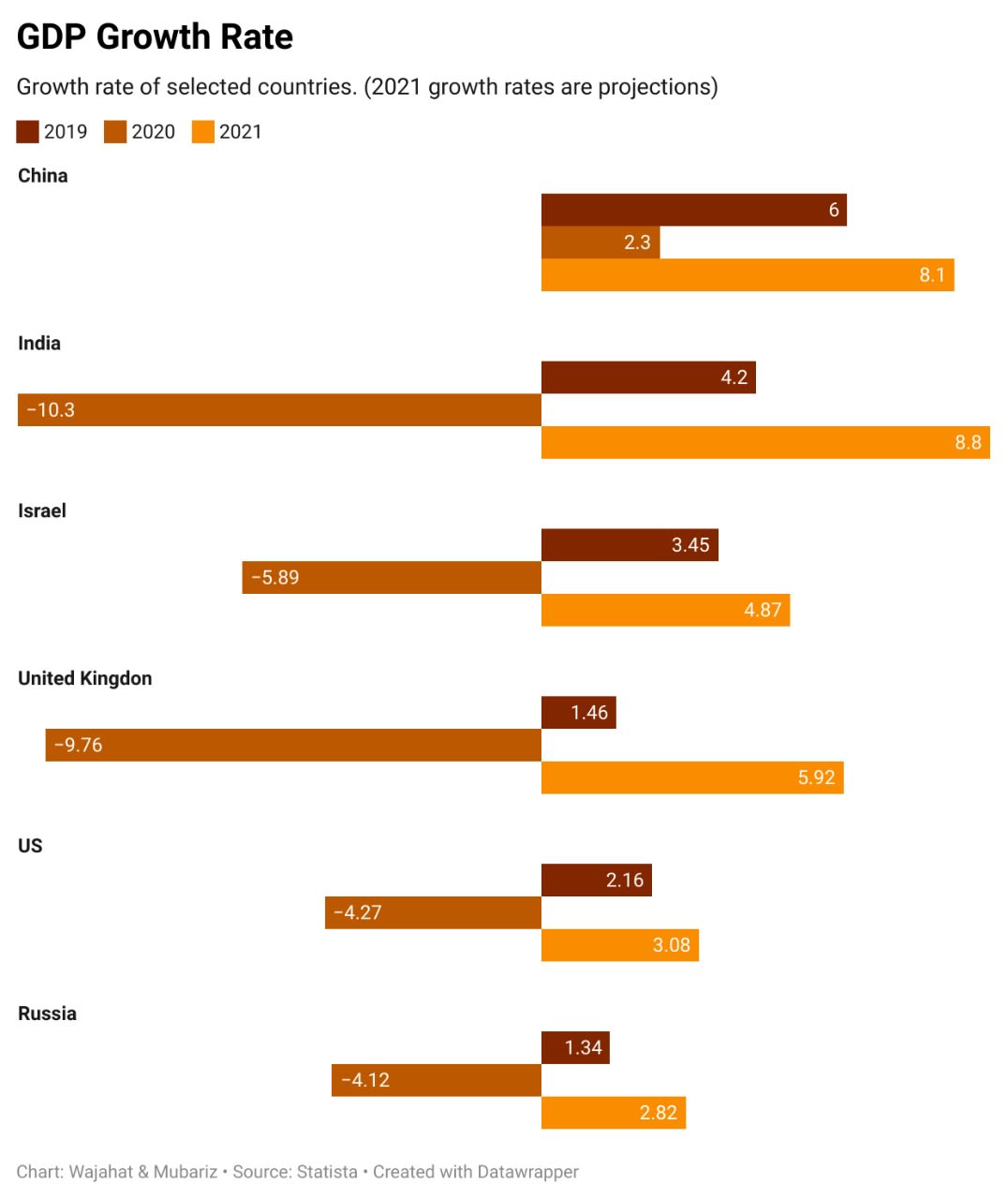

One way to look at the data is through the effect the global economy has had as a result of the pandemic. The pandemic and its crisis is truly global as no country has been spared the socio-economic losses it has brought.

Countries reliant on tourism, travel, hospitality, and entertainment for their growth have experienced particularly large disruptions. Emerging markets and developing economies have faced additional challenges with unprecedented reversals in capital flows as global risk appetite wanes, and currency pressures. While also having to cope with weaker health systems, and more limited fiscal space to provide support to their people. On top of that, several economies entered this crisis in a vulnerable state to begin with; sluggish growth and high debt levels already holding them down.

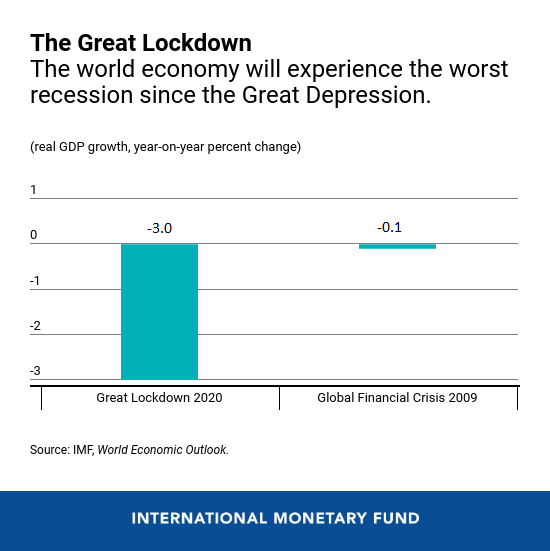

For the first time since the Great Depression, both advanced economies, as well as emerging markets and developing economies, have faced a recession. For the year 2020, growth in advanced economies was projected at -6.1 (IMF). Emerging markets and developing economies, with normal growth levels well above advanced economies, have also been projected to have negative growth rates of around -1.0 percent in 2020, and -2.2 (IMF). The income per capita is projected to shrink for over 170 countries and both advanced economies and emerging markets & developing economies are expected to only partially recover in 2021.

The US, UK, and their fair share

Prior to the pandemic, the U.S. economy was doing very well. Unemployment was at a 50-year low and inflation was also below the targeted 2.0%. However, the closure of a significant portion of the U.S. economy, ‘real’ GDP growth, fell during the second quarter by an astounding 31.40%. These numbers had not been seen since the Great Depression.

In 2020, the U.S. GDP contracted at a 3.5% annualized rate. It was the biggest contraction since 1946 and the first contraction since 2009 (Yahoo Finance). The economic crisis is unprecedented in its scale: the pandemic has created a demand shock, a supply shock, and a financial shock all at once (Triggs and Kharas 2020).

The U.S. economy is primarily driven by consumer spending. When consumers spend, companies’ profit and the economy is good. In early April 2020, 43% of businesses had temporarily closed. Almost all of the closures were a result of COVID-19, a survey from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) suggested. Moreover, in October 2020, there were 6.8 million more unemployed workers than there were in February 2020.

The economic impact of the pandemic has hit the UK particularly hard in comparison to its international counterparts. As of December 2020, figures for quarter three (July – Sept) have shown that the UK economy is still 9.7% below its pre-pandemic levels, more than double the decline seen in the US and the EU. In quarter two (Apr – June) the UK decline of 20.4% was steepest of all comparable countries and double the OECD average of 9.9%. Further, the most recent monthly GDP figures showed the UK ‘bounce back’ was continuing to slow even before further lockdown restrictions were announced, with monthly growth of only 1.1% into September. Even though the fifth consecutive month of growth, the pace continues to slow from 9.1 % in June, 6.4 % July and 2.1 % August (TUC UK).

What can be argued is that vaccine development led by countries such as the US and UK in the ‘developed’ world has not come out of the sheer goodwill of these states. There is a strong case to be made along the lines that these countries feel the need to protect their own interests and their own economic standing at the global level in the face of the pandemic. It has been a mechanism to ensure the power dynamic does not shift or have permanent changes, ones that are disadvantageous to the political and economic power of countries like the USA, UK, Russia, and China.

States around the globe have spent large sums during the virus' major active periods (2019-21) to mitigate its potential harm.

Some countries have had better progress than others - but it does not come as a surprise considering their economic stature and stability prior to the virus.

The Other Side of the Coin i.e. Russia & China

An interesting point of analysis is that of the vaccine development efforts made by Russia and China. Largely influenced by their recent history of power plays in a global political context, the COVID-19 realm has seen a similar politicization by these states as well.

Putin has stated that the Russian regulatory bodies had approved a COVID-19 vaccine developed by the Gamaleya Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology in Moscow, even though phase III trials of the vaccine had yet to be completed (Nature). And without a completed phase III trial, there have been worries that it will not be clear whether the vaccine prevents COVID-19 or not — and it will be difficult to tell whether it causes any harmful side effects, because of gaps in how Russia tracks the effects of medicines.

The effort put in to mask data and promote low efficacy vaccines has been largely influenced by the aspiration to open up the Russian economy, which is largely dependent on a mass labor force. The rapid development and rollout of vaccines can also be attributed to the negative growth rate of - 4.12% (GDP for 2020) for the Russian economy. It has been putting in large amounts of effort to ensure a swift transition back to normalcy and stability.

China plans to provide 10 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines to the global vaccine sharing scheme COVAX. Vaccines from Chinese firms are already being rolled out in several countries, including Brazil, Indonesia, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates. Dependent on the global trade network, China has promoted vaccines in developing countries (Reuters). It has also continuously exported its human capital to overlook development projects under its One Belt, One Road initiative which has pushed the Chinese state to provide swift protective measures to its officials.

China has essentially fast-tracked its vaccine development to create a (false) sense of control in order to ensure their economic interests are protected and remain on track with their quest for global political and economic dominance. Both China and Russia have used vaccine development and rollout as a means of acquiring soft power and influence in many developing countries around the world, motivated largely by their economic growth aspirations.

Moving forward:

Economic protection and prosperity have been a major influence in vaccine procurement, development, as well as deployment by major political players around the world. There have been reports on the likes of the US and UK placing blocks on the provision and development of vaccines to and in lower-income countries on the basis of patents and hegemonic control.

The decisions taken by the governments of states such as China, Russia, the UK, and the USA have clearly indicated an economically charged motivation behind vaccine efforts - staying true to their historical positionality as profit-interested and self-interested.

Our analysis presents a critical point of view when examining the current global vaccine drive - it is important to understand that motive and gain remain at the forefront of high-income countries' attempts at helping the global network. It is not apolitical and certainly not exempt of critique.